Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (2024) is due to be yet another box office bomb, part of a disconcerting trend where more and more blockbusters are failing to recoup their increasingly enormous budgets. One can only speculate as to why Furiosa has been a financial failure in spite of excellent reviews. Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), which Furiosa is a prequel to, was released nearly a decade ago and that film wasn’t the box office smash its most ardent fans remember it being. Another reason for Furiosa’s box office struggles is that film goers may have viewed it as just another franchise cash grab by Hollywood looking to take advantage of nostalgia for a pre-established IP from the 1980s, which audiences have begun to sour on. This is a shame as anyone who is familiar with the Mad Max films knows its entries in the 21st century have never relied on nostalgia to tell its stories. Since its inception 45 years ago, the Mad Max series has not been the result of a corporate committee making films in a boardroom like how most blockbusters have been produced over the last 20 or so years. Mad Max has been the result of one auteur’s vision: George Miller, one of the most underrated yet greatest filmmakers of his generation. His body of work is more than just Mad Max films, but they will be his legacy. Regardless of Furiosa’s box office struggles, the Mad Max franchise has never been about the revenue they generate on opening weekend. George Miller makes films which leave a lasting impact on our culture. Mad Max (1979) was Miller’s directorial debut. The film was made on a shoestring budget with a cast of unknown actors, yet Mad Max spawned a franchise which remains influential 45 years later.

Before George Miller created Mad Max and before he either wrote or directed celebrated family films like Babe (1995), Babe: Pig in the City (1998), Happy Feet (2006), and Happy Feet 2 (2011), he was just a kid from Chinchilla, a small rural town in Queensland, Australia. There was no television during Miller’s childhood. The only entertainment he had was the Saturday matinee at the local movie theater and comic books he bought from the general store. Miller and his peers would act out scenes from the movies they had watched and from the comics they read. Every Saturday night during his teen years, kids would take their cars for joyrides on Chinchilla’s main street. Among Miller’s cinematic influences were The French Connection (1971), which featured one of the first true great car chases in cinema, Stagecoach (1939), and Buster Keaton films.

George Miller’s yearning to become a film director didn’t waiver as he went through medical school at the University of New South Wales, where his brother made him aware of a film competition the university was holding. They had one hour to make a one-minute silent film. The winners of the competition would be given the opportunity to attend a free film workshop. The film entitled St. Vincent's Revue Film (1971) starred Nico Lathouris, who later would have a small role as a mechanic in Mad Max (1979) and co-wrote Mad Max: Fury Road and Furiosa with Miller. St. Vincent's Revue Film placed first in the competition and George Miller attended the free workshop in Melbourne where he met his future business partner and collaborator Byron Kennedy. The two young filmmakers sought to advance their careers together and they submitted a film they made, Violence in the Cinema, Part I (1971), a satire about movie violence to the 1972 Australian Film Institute Awards where it won the competition’s silver award. In the years leading up to the making of Mad Max, Miller and Kennedy worked on various Australian film productions picking up valuable experience.

George Miller and Byron Kennedy began their filmmaking careers at the perfect time. In 1970, the Australian Film Development Corporation (which has existed under different names since 1970) was established under Prime Minister John Gorton’s government to revive the country’s film industry which was all but dead by the end of the 1960s. The goal was not only just to revive Australia’s film industry, but to promote the country’s culture within its own borders and abroad by funding Australian filmmakers. That same year, the Australian Classification Board was established, which lifted the onerous restrictions on what could be depicted in films. The Australian Classification Board created a ratings system similar to the United States’ MPAA rating system after the Production Code was lifted. The ratings were G (General Exhibition), NRC (Not Recommended for Children), M (Mature) and R (Restricted to audiences aged over 18). Much like the MPAA’s rating system, film ratings in Australia have changed over time, but under this new paradigm Australian filmmakers, much like their American counterparts were now able to make movies with more risqué content if they chose to.

The Australian government funding low budget films and abolishing their strict censorship regulations revitalized Australian cinema almost overnight. A generation of Australians who grew up watching movies in the theater and on television finally had the opportunity to make films of their own. They didn’t let it go to waste. From 1970 to 1985, Australian filmmakers produced 400 films. It was known as the Australian New Wave. These filmmakers utilized Australia’s vast and diverse landscape to explore their cultural identity. They focused on the contradictions between Australian cities and The Outback. The country’s dark side was also explored, and the people are often portrayed as just as violent and threatening as the land itself. Australian filmmakers took full advantage of the country’s new R rating and made low budget action, horror, and comedy films which were far more violent and sexual than the ones produced under the previous repressive system. Critics of the era considered these exploitation films to be low rent and vulgar and panned them or ignored them altogether. Audiences on the other hand loved these movies. Decades later, these exploitation films were dubbed Ozploitation, an amalgamation of Australian and exploitation. It was American filmmaker Quentin Tarantino, a fan of Ozploitation films, who first referred to them “Aussieploitation” while being interviewed for the documentary Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation! (2008) (Author’s note: there’s a lot of nudity in this trailer clip). Mark Hartley, the documentary’s director, then shortened the term to Ozploitation. Some film scholars believe Australian New Wave and Ozploitation are one and the same as both movements coincided with one another. Other scholars believe they are separate and some believe Ozploitation films are a distinct subgenre of the Australian New Wave. Quentin Tarantino used rather colorful language when describing what Ozploitation films are “…marauding packs of bullies roam the highway looking for people to fuck with.”

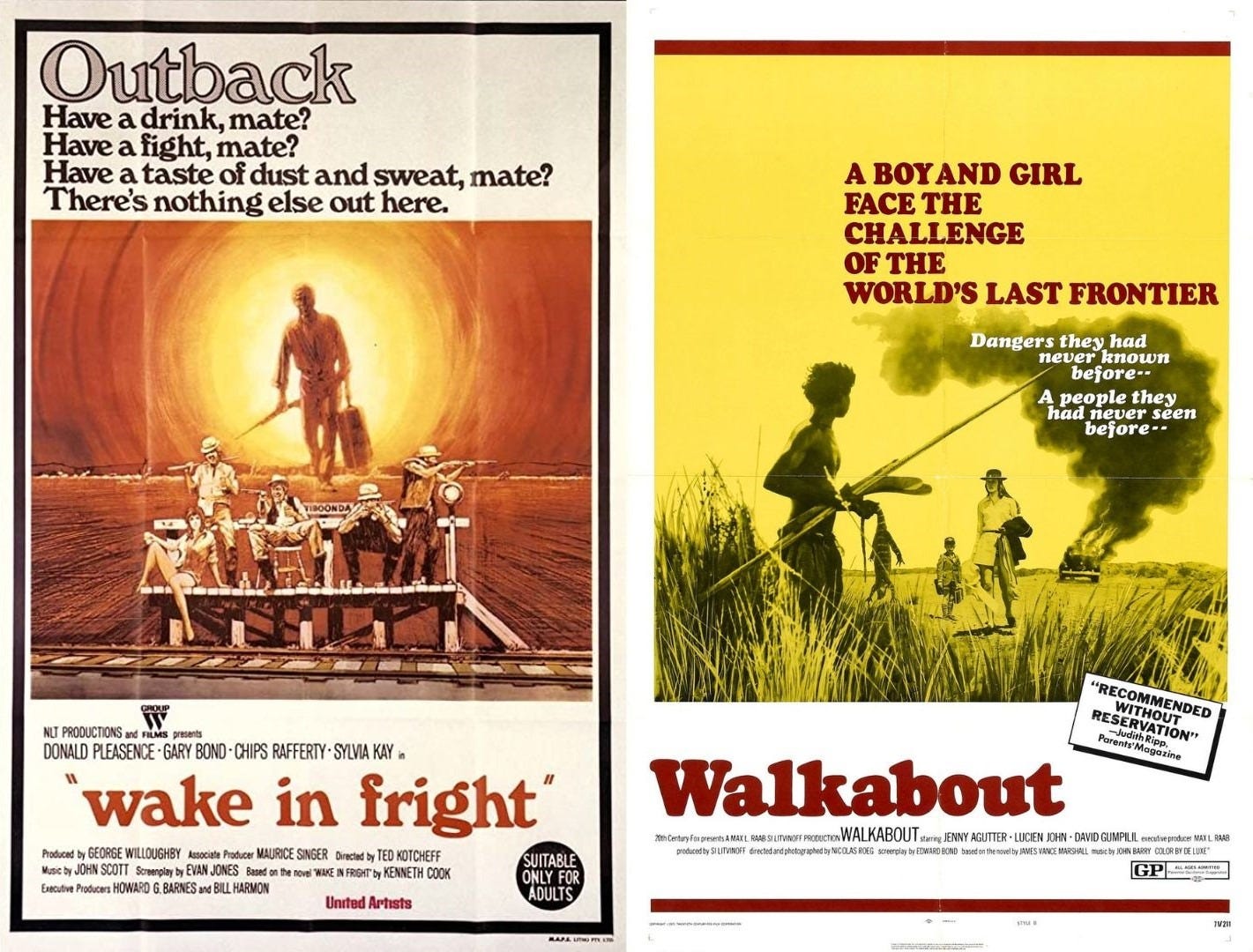

In 1971, Wake in Fright and Walkabout kickstarted the Australian New Wave when they premiered alongside each other as Australia’s entries at the 24th Cannes Film Festival. Walkabout is about a white brother and sister from Sydney, who after being abandoned by their father in The Outback encounter an Aboriginal teenager who is on his walkabout. The Aboriginal teenager helps the siblings survive in the harsh Outback and they form a bond which transcends their cultural backgrounds. Wake in Fright is a film about a middle-class schoolteacher from Sydney who gets stuck in a small, isolated town in The Outback inhabited by violent alcoholics. The schoolteacher is repulsed by the men’s drunken debauchery, yet he can’t himself but join them in their dangerous activities. He binge drinks alongside them and participates in a kangaroo hunt. Wake in Fright is now regarded as a classic of Australian cinema and one of the first Ozploitation films, but the Australian public rejected the movie when it was released due to the politically incorrect portrayal of The Outback and its people. However, Wake in Fright received rave reviews from the foreign film critics in attendance at Cannes who loved the film’s gritty depiction of Australian life. Walkabout also received rave reviews from the critics at Cannes for its romantic depiction of Australian life. Australian cinema and all its glorious contradictions had finally arrived on the world stage.

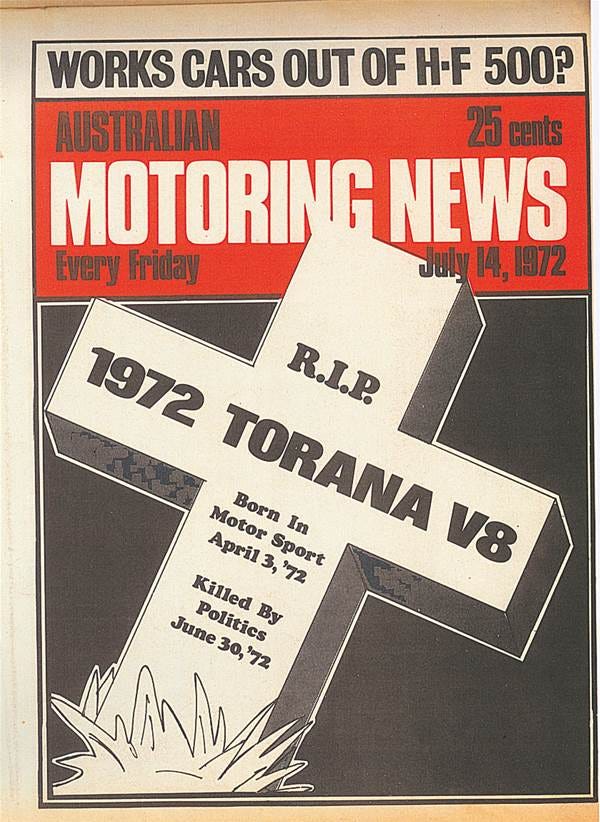

Australia’s car culture was also a popular topic during the New Wave, particularly its destructive impact on Australian citizens. After World War II, car accident fatalities and injuries in Australia skyrocketed and peaked during the 1960s and 70s which coincided with rising automobile ownership rates. In 1972, the rising popularity of inexpensive muscle cars like the Valiant Charger, whose powerful V8 engine could push the car to a top speed of 140 mph, were blamed for the increase in injuries and road deaths just as they peaked in popularity in what became known as the “Supercar Scare”. The combination of government pressure on the auto industry and The Oil Crisis killed the Australian muscle car market, much like it did in the United States. However, it took some years for muscle cars to leave Australian and American roads, and they remained etched into both country’s popular consciousness.

Deaths and injuries from car accidents didn’t decline until the Australian government fixed the greater systemic problems which existed on the roads. In 1970, Victoria mandated the use of seatbelts, followed by New South Wales in 1971. In 1972, seatbelts were made mandatory throughout the whole country. Safety standards to improve braking systems, lights, and mandating all motorcycle riders wear helmet were enacted. From 1976 to 1988, Australian states gradually passed laws empowered the police to perform random breathalyzers tests.

Unlike other action films, gun violence and elaborate hand to hand combat sequences are not as frequent in the Mad Max franchise. Cars are the source of the Mad Max series’ violence and that’s no coincidence. In the years leading up to Mad Max’s production, George Miller split his time between working on small film productions and working as an emergency room doctor where he saw firsthand how cars were the primary cause of violence in Australia. Many of the patients Miller treated had been injured in car accidents and many of them certainly died as Miller tried to save their lives. Miller also lost several of his friends in car accidents when he was a teenager. In Chinchilla, the roads were long and flat and there were no speed limits. Underneath the Mad Max series’ bombastic action sequences, colorful names and costumes, there is a profound sense of tragedy, suffering, and loss. Many of the series’ most thrilling and saddest moments involve vehicle chases and wrecks. Mad Max still compels viewers across the world 45 years later because it connects the tension at the heart of car obsessed countries like the United States and Australia. Cars can be a great source of freedom. It gives drivers the sense that they can go wherever they want. Muscle cars, sports cars, trucks, and motorcycles look cool, and their high speeds appeal to young men’s delusions of masculine grandeur. The liberation these vehicles supposedly offer comes at a great cost. Driving a car or any sort of vehicle increases the odds that whoever is inside will meet a violent end on the road.

In 1978 George Miller and Byron Kennedy founded their own production company, Kennedy Miller Productions, to facilitate the making of their first feature length film, Mad Max. Miller and Kennedy would co-write the story, while Miller would direct. Although Miller had experience working on film productions, he had no experience writing a screenplay, so he recruited The Australian’s finance editor James McCausland to help him co-write the script even though he had no screenwriting experience either. McCausland was hired by Miller after he read film critic Pauline Kael’s book Raising Kane, where he learned many American screenwriters had journalism backgrounds. Miller educated McCausland on the principles of cinema by taking him out to the movies and discussing their favorite westerns and action films. In a 2006 op-ed for The Courier-Mail regarding Peak Oil, McCausland wrote about how witnessing The Oil Crisis’ effect on Australians gave him inspiration for Mad Max’s postapocalyptic setting. “A couple of oil strikes that hit many pumps revealed the ferocity with which Australians would defend their right to fill a tank. Long queues formed at the stations with petrol – and anyone who tried to sneak ahead in the queue met raw violence… George and I wrote the script based on the thesis that people would do almost anything to keep vehicles moving and the assumption that nations would not consider the huge costs of providing infrastructure for alternative energy until it was too late.”

With Mad Max, George Miller resolved to make a film which was in his words “pure cinema” and “a silent film with sound” which would be reminiscent of the action-packed Buster Keaton films he loved like The General (1926). Alfred Hitchcock’s ability to make films with a simple story so non-English speaking audiences would be able to understand what was happening onscreen without the use of subtitles was also something Miller picked up on. Miller and Kennedy eventually raised $350,000 from investors to finance Mad Max’s production. They also raised additional funds by performing emergency house calls with Kennedy driving Miller around to treat patients in their homes. The film’s tight budget meant Miller and Kennedy had to be incredibly resourceful during production.

George Miller wanted an American actor to play Max so the film could be marketed beyond Australia’s borders, but Miller quickly realized this would be far too expensive and decided to cast an Aussie instead. Mel Gibson, a 21-year-old actor who had just graduated from Sydney’s National Institute of Dramatic Art was cast as Max after he impressed Miller for showing up to his audition with a heavily bruised face, which he received the night before in a fistfight. Mad Max would be his second film, and his salary was $10,000. In a roundabout way, Miller ultimately achieved his goal of casting an American actor in the lead role. Gibson was born in New York and emigrated with his family to West Pymble, a Sydney suburb when he was 12. Although Gibson was an American, his formative years living in Australia gave the Mad Max films an authenticity they would have lacked if an American had been cast. Hugh Keays-Byrne was cast as the film’s main antagonist Toecutter on the condition that his friends were cast alongside him as members of Toecutter’s gang. Keay-Byrne and his friends drove their motorcycles from Sydney to Mad Max’s shooting locations in Melbourne because Kennedy and Miller didn’t have enough money to fly them and their bikes in. During their journey, the men rehearsed how to act like a biker gang, which got them in the right mindset to play their roles. Real life members of the Vigilantes and Hell’s Angels motorcycle clubs were hired to round out the rest of Toecutter’s gang and to provide some stunt work. Kennedy and Miller didn’t have enough money to pay them a salary, so the bikers, extras, and other members of the crew were paid in 24 packs of beer. By all accounts there were no qualms with this arrangement.

Principal photography on Mad Max was scheduled to be shot over the course of ten weeks. The last four weeks of shooting was to be dedicated to filming action sequences, while the first six weeks were dedicated to non-actions scenes. However, the actress playing Max’s wife Jessie, Rosie Bailey, and lead stuntman Grant Page broke their legs in a motorcycle accident after an 18-wheeler cut them off as they were speeding to that day’s filming location. The accident brought filming to a screeching halt for two weeks as Miller and Kennedy scrambled to find a replacement. Joanne Samuel was ultimately cast to replace Bailey and Page recovered enough to perform his stunts in a cast. The film’s difficulties proved to be too much for Miller and he quit part way through filming. The fast-paced atmosphere of working in emergency rooms treating people with horrific injuries did not prepare Miller for how to deal with the chaos of a movie production. Byron Kennedy reached out to director Brian Trenchard-Smith and asked if he would be willing to take over the production. Trenchard-Smith suggested to Kennedy that he hire a good first assistant director to help Miller. Miller returned to the director’s chair a couple of days after he quit and Ian Goddard, one of the top motorcyclists in Europe, was hired as first assistant director and aided Miller in coordinating the vehicle stunts. Goddard and his team’s preparation ensured that nobody was injured during shooting. Despite this, Miller lost the respect of his crew when he temporarily quit. Mad Max was a guerrilla filmmaking experience for George Miller and his crew. The car chase scenes were shot without any permits and the crew did not utilize walkie talkies out of fear the police would pick up the radio frequency. However, it is hard to make an action movie out in the open without attracting attention and the Victorian Police became aware of the production. Instead of shutting the production down, the Victorian Police aided the filmmakers by shutting down roads for filming and escorting cars to and from shooting locations.

Geoge Miller was 32 years old when he began filming Mad Max. It would be his directorial debut. One can’t help but think that Miller believed this could possibly be the last film he ever directed. He lays everything on the line in Mad Max’s opening scene, a thrilling car chase between The Nightrider (Vincent Gil) and members of the Main Force Patrol (MFP), a fictional police force charged with combating the growing number of criminals on Australia’s roads. As the members of the police crash their cars pursuing The Nightrider, we get glimpses of Max getting ready as he waits for The Nightrider to cross paths with him on the road. Miller builds anticipation for Max’s reveal by never fully showing his face. When Max finally joins the chase, he demonstrates that he is the best driver on the road with his skill and utter fearlessness and The Nightrider quickly realizes he has met his match. The Nightrider and his female companion are killed in a blazing crash when Max diverts their car into a roadblock. The crash and their deaths last a mere few seconds on film but took three days to shoot. Aside from a brief flash of The Nightrider’s eyes bulging out their sockets, his death is not particularly bloody. Much of the graphic violence in Mad Max happens off screen. Miller uses similar techniques to ones Steven Spielberg utilized in Jaws (1975). Miller only shows blood briefly before cutting away and he cuts away immediately before something gory happens. This a allows the viewers to imagine the full extent of the violence and is much more powerful than displaying it all onscreen for a prolonged period of time.

Max’s face is finally revealed when he gets out of his car to observe the smoldering wreckage. The zoom in on Mel Gibson’s boyish face is reminiscent of the star making shot of John Wayne director John Ford used in Stagecoach, a major influence on Miller. Although Mad Max was his first film, George Miller already was a master at how to create a star with just one shot and he already knew how to film an action-packed car chase on a shoestring budget.

Mad Max isn’t really a post-apocalyptic film. Part of what makes the Mad Max series so rewatchable is that it isn’t trapped in its own continuity unlike many other blockbuster franchises. The five Mad Max films can be watched in any order because each entry is its own self-contained story. However, it’s very clear that Mad Max is the first film in the saga’s timeline as it takes place just as civilization is about to fall. Unlike later installments of the Mad Max franchise, all the characters in the first film wear clothes which fit the time period it was filmed. Even the bikers are outfitted how outlaw motorcycle clubs have always dressed. The vehicles in the film (except for the black Pursuit Special) are normal as well. The heavily modified vehicles adorned with weapons and armor and over the top costumes would not be introduced until the sequels. In Mad Max there are still a couple of gas stations, a diner, mechanic shops, and a nightclub. All this infrastructure is badly decayed and what’s left of the small towns littered across the landscape are barely standing. The presence of a police force tells the viewer there is some semblance of a government left, but it’s obvious they are a quickly crumbling last line of defense.

While Max is celebrated by his fellow officers for stopping The Nightrider and for being the best officer on the force, he is deeply conflicted about the ever more violent nature of his job. He fears the death-defying car chases are causing him to go mad and will lead him to becoming no different than the marauders he’s charged with stopping. When away from the police force, Max is a dedicated family man who spends time at his home with his wife Jessie and their infant son Sprog (Brendan Heath), Sprog is Australian slang for child so technically the character doesn’t have a name. It’s these quiet moments which give the audience a keen insight into the character’s psychology and provide hints that Mel Gibson would become much more than an action star in the future. Max is ultimately a good man at heart, but his family is the only thing keeping him from losing his grip. Max might hate being a policeman, but he’s right at home whenever he’s behind the wheel.

Max’s superiors give him a heavily modified Ford Falcon XB which is outfitted with the last of the department’s V8 engines as a way of enticing him to stay on the force. The V8 is treated with godlike reverence by the film’s characters and it is the first of many myths the Mad Max series establishes. Max’s car dubbed the Pursuit Special (sometimes called the V8 Interceptor), has gone on to become one of the most iconic vehicles in cinema history.

Meanwhile, The Nightrider’s motorcycle gang led by Toecutter arrive in a small town to claim his body. They terrorize and bully the townspeople and attack a young couple who try to escape in their car. The gang destroys their car and pulls the couple from the vehicle. It is not shown on screen, but it is strongly implied the young man and woman are gang raped. Rape was among the many taboos filmmakers in American and Australia broke in the 1970s. This trend was fueled by the Tate-LaBianca Murders committed by members of the Manson Family in August 1969. One of the victims, Sharon Tate was a rising young Hollywood starlet who was eight and a half months pregnant when she was stabbed to death in her own home. The murders shocked America and the world at large and it led ordinary people to fear that if a Hollywood star could be killed in her home by a gang of low lifes, then they could fall victim to the same fate as well. Filmmakers tapped into this fear and many horror and exploitation films of the 1970s graphically depict families being brutalized and women being raped. In Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), a woman is gang raped while her husband is forced to watch. In Straw Dogs (1971), a young couple who move to a small town are terrorized by the locals and the woman is raped on two separate occasions. In Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972), a young woman is raped and killed by a gang of criminals who unknowingly take refuge in her parents’ house after the act. Upon discovering what has happened to their daughter, the parents brutally murder the gang. In The Hills Have Eyes (1977), another Wes Craven film, a family is attacked in their RV by cannibals during their vacation. Several of the family members are gruesomely murdered and one of the female members is raped. Men were not spared from the trend either. The scene in Deliverance (1972) where Ned Beatty’s character is sodomized in the backwoods is still one of the most shocking moments in cinema history. In And Justice for All (1979), a lawyer played by Al Pacino has a young man for a client who has been jailed for a crime he hasn’t committed. Later in the film, the young man reveals to Pacino’s character that he has been gang raped by other inmates.

Max and his partner Goose (Steve Bisley) come across the aftermath of the assault. They arrest a member of Toecutter’s gang, Johnny the Boy (Tim Burns) who was left behind at the scene, but no charges are pressed against him or the other bikers because the young couple is too traumatized to testify. Johnny the Boy is also deemed not mentally fit to be charged with a crime. Another common theme in film during this time was for a criminal who is obviously guilty for his crimes to be let off on a technicality. In Dirty Harry (1971), evidence against the Scorpio (Andy Robinson) serial killer is dismissed in court after San Fransico Police Inspector Harry Callahan (Clint Eastwood) tortures him into confessing the location of a teenage girl he kidnapped by stepping on a bullet wound in his leg. These films reflected the public’s assumption that criminals were hiding under excuses to dupe a liberal legal system into letting them off the hook for their crimes. This might be seen as a reactionary viewpoint now, but homicide rates in both America and Australia exploded during the 1970s, a trend which would continue until the early 1990s. People’s belief that the government was failing to protect them and their communities during this period was not unfounded.

Toecutter’s gang isn’t just obsessed with wreaking havoc on innocent people. The bikers know that Max and members of the MFP are responsible for The Nightrider’s death and they intend to take their revenge. They ambush Goose on the road and burn him alive inside of his vehicle. When Max visits Goose in the hospital and sees his scorched body, he doesn’t swear revenge like most action heroes do. Instead, he pleads with his superior Captain Fred "Fifi" Macaffee (Roger Ward) to let him resign so he can keep what little is left of his sanity. However, Max is talked out of quitting by Fifi who tells him the world needs heroes. Fifi lets Max take a vacation to clear his head and to reconsider his resignation. Max takes Jesse and Sprog on a road trip across Australia. While on a picnic with Jesse, Max tells her how much he loves her. During the trip, Max stops at a mechanic’s shop to fix his van’s spare tire and Jesse takes Sprog to an ice cream shop nearby where they are confronted by Toecutter and his gang. Jesse manages to escape with Sprog and Max takes them to a family friend, May Swaisey (Sheila Florence), an elderly woman who lives on a farm with her mentally disabled son, Benno (Max Fairchild).

Mad Max is an action film, but in the lead up to the climax, elements of horror are introduced as an ordinary family’s worst nightmares come true. Toecutter and the bikers track the family down and chase Jesse while she’s on a walk in the forest near the farm. The gang manages to take Sprog hostage while Max goes looking for her. Jesse is then cornered by the bikers who threaten Sprog’s life in front of her, but a rifle toting May steps in and forces the gang to relinquish Sprog. The three escape in the family van, but it breaks down on the highway. Jesse takes Sprog and makes run for it as Toecutter and his gang pursue them on their motorcycles. Miller cuts away at the point of impact when the bikers run Jesse and Sprog over. We only see the aftermath when Sprog’s detached shoe and ball roll into the frame. Max arrives only moments later. At the hospital, Sprog is pronounced dead and Jesse, who has lost her arm and is in a coma is not expected to survive.

The personal nature of Max’s battle with the bikers is why Mad Max still resonates with people to this day. If the bikers didn’t disfigure his partner or kill his family, then Mad Max’s action scenes would be far less intense. Miller establishing the loving relationship between Max and Jesse also separates Mad Max from its revenge film counterparts. The audience fully sympathizes with Max and are rooting for what he is about to do next. When Max’s wife and son are killed, it severs what’s kept him linked to humanity. The police are no longer seen in the film after Max leaves for his ill-fated vacation and they never appear again in the series. The rapists and pillagers who roam the highways are victorious and what little civilization is left has fallen away, mirroring the destruction of Max’s own family. In the Mad Max mythos, the nuclear war between the Soviet Union and the United States is the epilogue to society’s collapse not the cause.

In the following scene, Max dons his leather police uniform, grabs a sawed-off shotgun, and steals the Pursuit Special from the police station. Max ambushes members of Toecutter’s gang after they steal oil from a tanker. Max forces two of the bikers off a bridge and into the river below. The remaining bikers fall victim to terrible crashes. One crash in particular is really gnarly as the front tire of a motorcycle strikes a stuntman in the back of the head and neck. However, Max himself is later ambushed when he goes to confront Toecutter and the surviving members of his gang. He’s shot in the leg and as Max reaches for his shotgun, a biker runs over his right arm. However, Max’s thirst for vengeance runs into the deepest parts of his soul. When the biker comes back to finish the job, Max is able to get to his shotgun and blasts the biker off of his motorcycle. Max wills his way back to his feet as Brian May’s (not the guitarist from Queen) score, which is reminiscent of a classic western film from the 50s and 60s kicks in. Toecutter and Johnny Boy, the last remaining members of the gang, flee as Max gets back into his car. As Toecutter desperately tries to escape from Max, he is struck head on and crushed by a semi-truck. Later, Max confronts Johnny Boy who is stealing a motorist’s shoes at the scene of a car accident. Johnny Boy denies killing the motorist and says he’s not responsible for killing Max’s family because of his mental illness. Max responds by handcuffing Johnny Boy’s ankle to the wrecked car and creating a fuse which will ignite the gasoline leaking from the engine. Max hands Johnny Boy a hacksaw and tells him it will take ten minutes for him to cut through the handcuffs, but that won’t be enough time for him to escape before the car explodes. Max tells Johnny Boy his only chance of surviving is to cut his foot off, which will only take five minutes. As Max drives away, the car explodes in the horizon behind him.

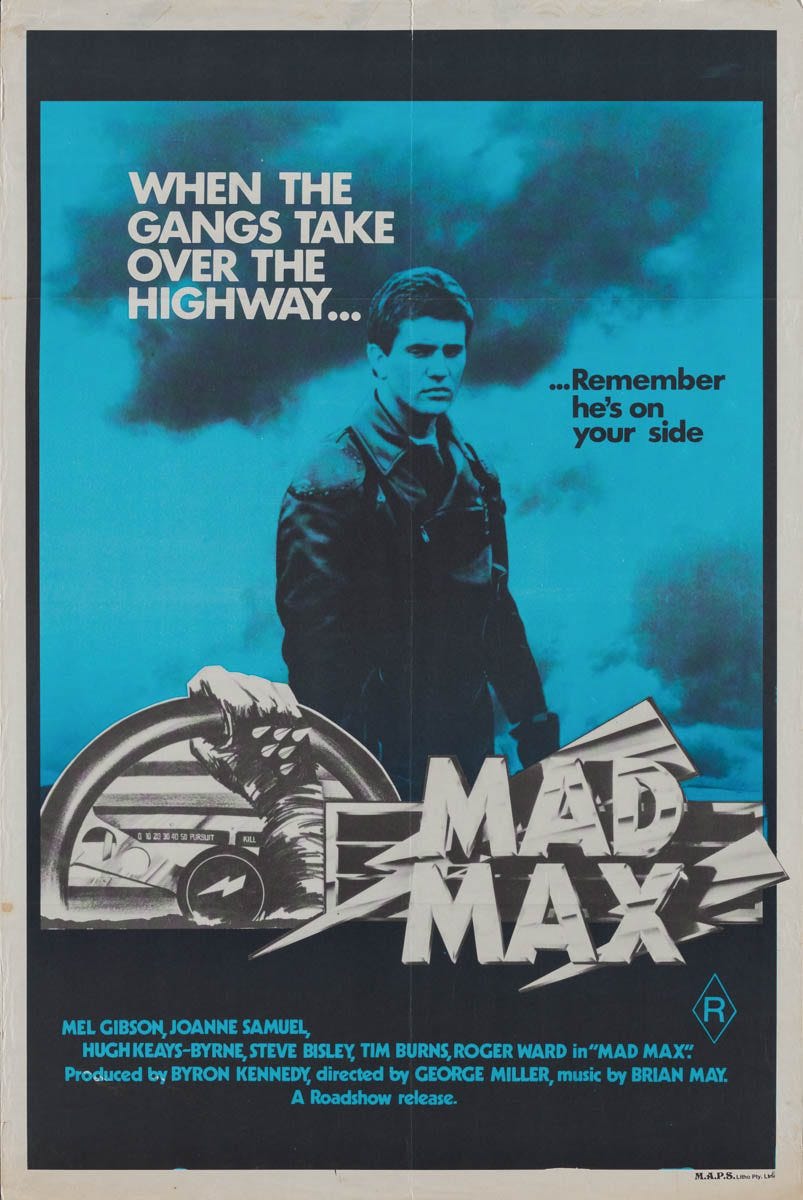

Mad Max was released in Australia in April 1979. It would be released in the United States in various theaters throughout 1980. To say critics hated it would be an understatement. Australian critic Phillip Adams compared the film to Mein Kampf. The New York Times Tom Buckley called Mad Max “ugly and incoherent” with obvious homosexual overtones”. However, Mad Max proved to be an underground hit and has grossed over $100 million worldwide since its release. With a budget of $350,000, Mad Max held the Guinness World Record for most profitable film of all time until The Blair Witch Project (1999) broke it 20 years later. George Miller observed years later that people from around the world connected with the film because they saw their country’s own cultural archetypes in Max. The Japanese saw him as a samurai, Scandinavians saw him as a viking, and Americans saw Max as a cowboy.

1979 marked the year when Australian culture, once isolated by the continent’s remoteness, finally broke through into the rest of the world’s mainstream. Australian rock band AC/DC released their commercial breakthrough album Highway to Hell (1979) and Mad Max rode the Australian New Wave to success unseen in the history of independent films. George Miller’s youth spent immersed in Australia’s thrilling yet dangerous car culture, his love for cinema, and his experience working in emergency rooms treating car accident victims made him the only person who could create a character in a franchise which is uniquely Australian, yet still appeals to people all over the world 45 years later.