On April 16, 2023, at an event hosted by musician Sarah Perrotta an old man in a wheelchair facing a piano mumbles into the microphone to announce the song he is about to play. His speech is almost incomprehensible. The old man is hunched over in his chair. A hunch created in part by decades of sitting in front of a keyboard or piano for hours on end. His beard is long and scraggly. The old man then plays “Sophisticated Lady”, a Duke Ellington number. His frailty belied the fact that he was still a musical genius. It was the final public appearance by Garth Hudson, the last surviving member of The Band, one of the most influential groups in this history of rock music. He died on January 21, 2025, in a nursing home in Woodstock, New York where he had been living since the death of his wife, Maud in 2022. Garth Hudson was 87.

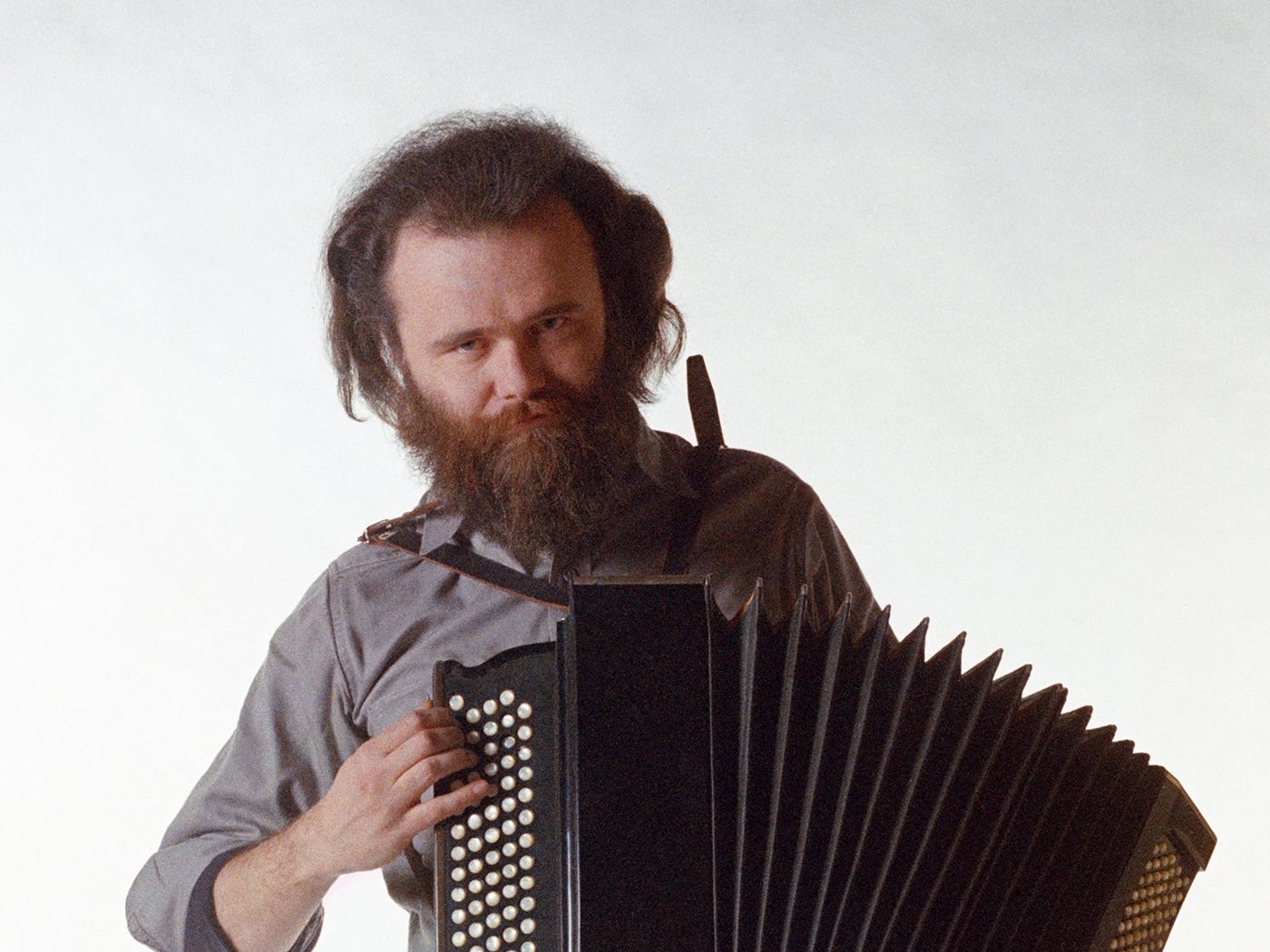

Garth Hudson’s final performance perfectly distills what kind of person he was. Hudson was not well spoken because English was not his first language. Music was, and not many people have been as fluent in this language as Hudson was. He was born on August 2, 1937, in Windsor, Ontario, Canada and moved to London, Ontario with his family three years later. His first exposure to music came from his father Fred, a World War I pilot, who was a drummer and played the reed and his mother Olive, who played the accordion and piano instruments her son would master. Hudson and his father were fans of hoedown music, a bluegrass genre originating from the Appalachian region of the United States, which was accompanied by people dancing the jig or clogging. By the time he was twelve years old Garth Hudson was already proficient in the accordion, and he joined a country band. During his youth, Hudson also played the piano and organ for the Anglican church his family attended and at his uncle’s funeral home. This laid the groundwork for one of popular music’s unheralded geniuses. Hudson would eventually become proficient in the saxophone, and he named tenor saxophonist Clifford Scott as his primary saxophone influence during The Band’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction speech.

Unlike many rock musicians, Garth Hudson was classically trained. He majored in music at the University of Western Ontario and took piano lessons from Clifford von Kuster, the university’s Dean of Music. One of Hudson’s early teachers, Nellie Milligan, was another major influence on his style. He also took organ and piano lessons from Thomas C. Chattoe, a British World War I veteran who moved to Canada ten years after the war and became the musical director for the Metropolitan United Church in London, Ontario. However, Hudson admitted that his fondness for improvising prevented him from becoming a great classical musician. He left the University of Western Ontario after one year to pursue a career in a newly burgeoning music genre called rock and roll.

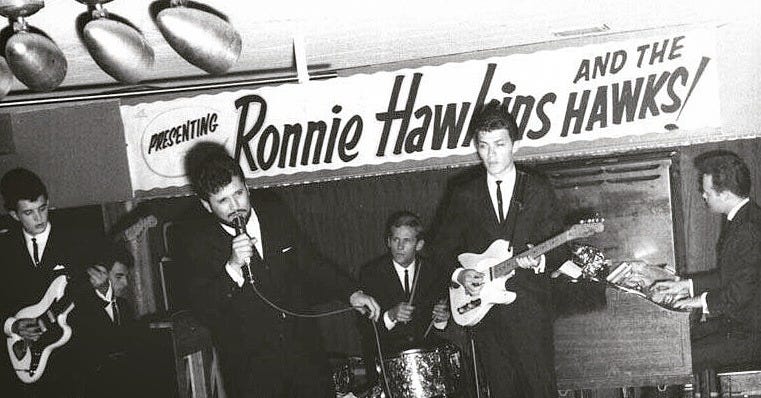

Garth Hudson cut his teeth playing the organ or piano in various bands in Ontario and Detroit, Michigan in the late 1950s and early 60s. In 1962, he caught the attention of rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins, who had become well known in the Toronto music scene despite never achieving sustained mainstream success in his native United States. Hawkins invited Hudson to join his backing band The Hawks which featured Robbie Robertson on the guitar, bassist Rick Danko, pianist Richard Manuel, and drummer Levon Helm. Hudson agreed to join so long as they bought him a Lowrey Festival organ. Hudson’s parents, on the other hand, believed their only child was wasting his life and musical education on rock and roll and refused to let him join the band. Hawkins assured the Hudsons that Garth would be giving the band music lessons for $10 a week and that their performances were serious work and not just an excuse to drink at a bar. Hudson took Richard Manuel under his wing, and it wasn’t long before the duo found their groove with Hudson providing the lead melody and Manuel providing the rhythm. The addition of Hudson also expanded The Hawk’s musical horizons beyond rockabilly and R&B. According to Ronnie Hawkins, Hudson would play notes the rest of the band had never heard before, but those notes fit perfectly with whatever they were playing.

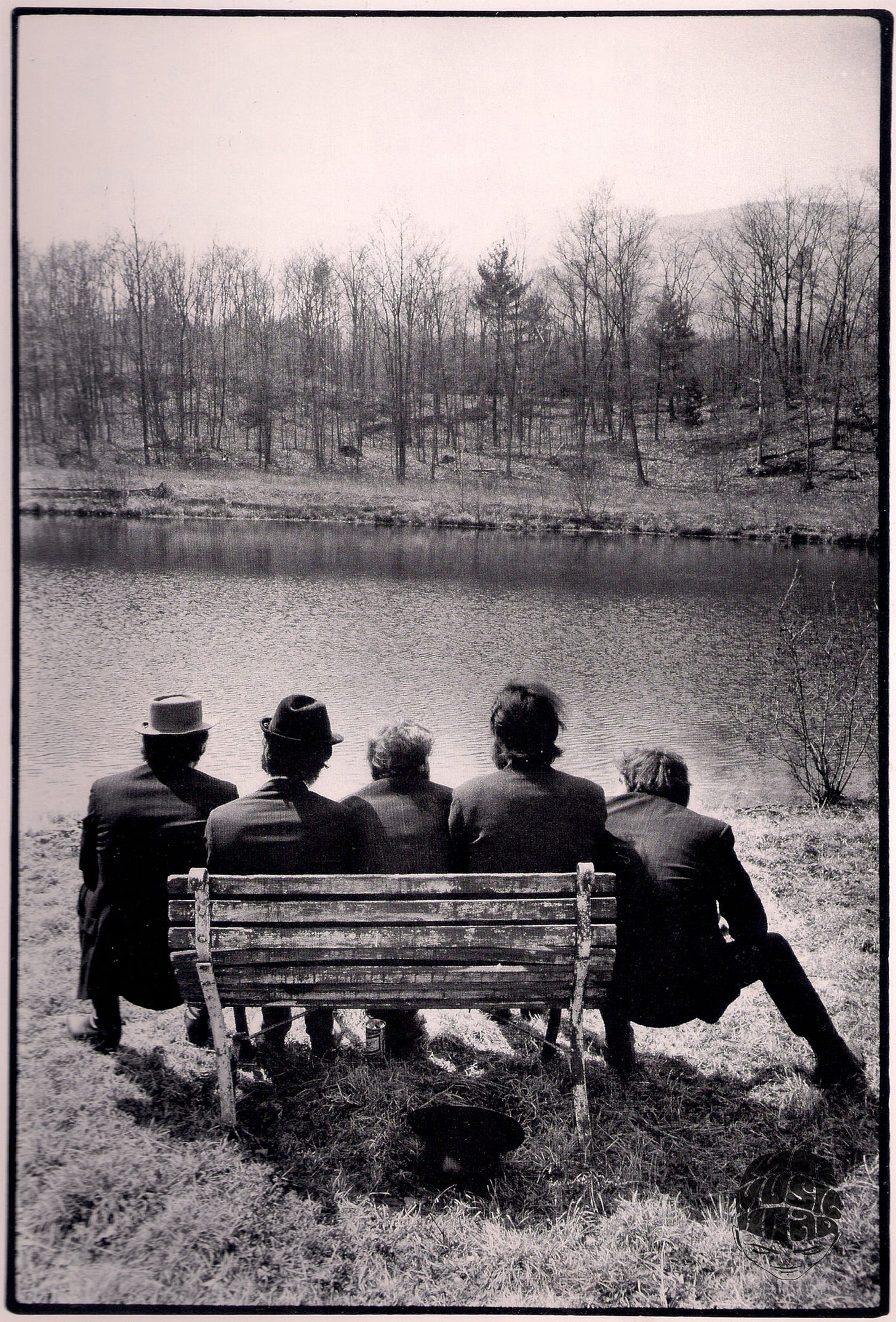

Within a year of Hudson joining The Hawks, they decided to split from Hawkins and go their own way. The Hawks would not receive their most famous name until they backed Bob Dylan on his seminal tour in 1965 and 1966 where they helped Dylan achieve new musical heights in the face of hostile folk audiences who were upset over his going electric. The men bonded in the face of this hostility, but Levon Helm became so despondent he temporarily left The Hawks after the tour to work on an oil rig. Fans were unaware of The Hawk’s history in Toronto and as the tour progressed, they began referring to them as The Band and the new moniker stuck.

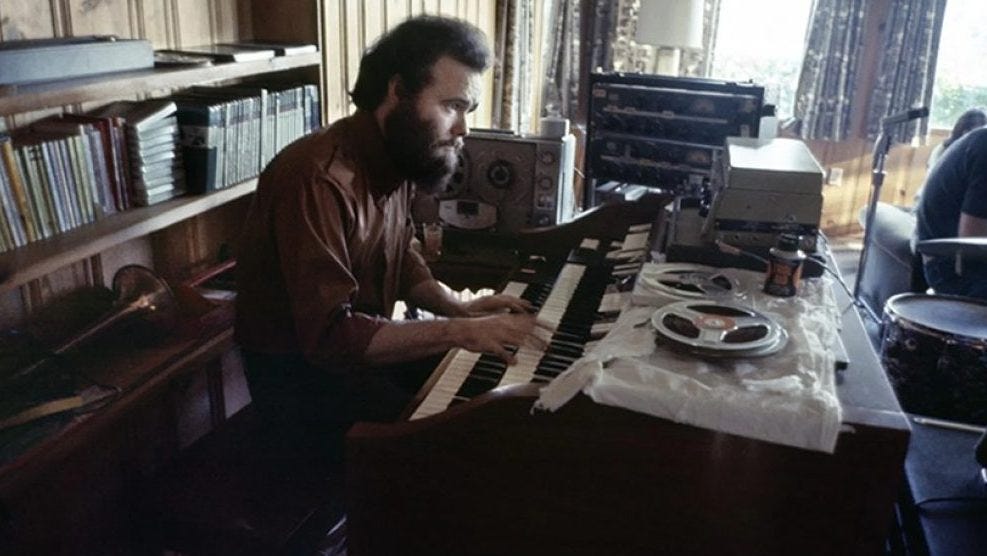

The eclectic influences of Garth Hudson were the secret to The Band’s unique sound, which many bands have tried and failed to emulate. When Bob Dylan took a sabbatical from touring to recover from injuries incurred in a motorcycle accident, Garth Hudson took a leadership role within The Band and set up a studio in the basement of Big Pink, a house with distinctive pink siding in West Saugerties, New York that he, Rick Danko, and Richard Manuel rented. The mixture of folk, country, and blues music The Band and Bob Dylan recorded at Big Pink during the summer of 1967 would change the course of rock and roll. That wasn’t their intention at the time. Dylan and The Band just wanted to get back to just playing music as friends and they never thought these jam sessions would see the light of day. Luckily, Garth Hudson placed a tape recorder on top of his organ. He was the only one who realized the songs The Band and Bob Dylan were playing needed to be preserved. Over 100 songs were recorded during this period. At first most of the songs were covers, but eventually Dylan and The Band wrote and recorded their own compositions. According to Hudson, they were so in tune with one another they were able to compose songs on the spot, one of which was “Sign on the Cross”.

During the late 1960s, rock artists played music influenced by psychedelics drugs. The lyrics of songs like Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” reflected how these drugs were warping the minds of these artists. The guitar solos and jam sessions on stage grew longer and longer, and the artists dressed up in colorful hippie clothing. However, as the flower power era drew to a close, rock and roll needed to evolve away from that image and that sound in order to stay relevant. The Band gave rock and roll the way forward. Although The Band’s first album, Music from Big Pink (1968), was not a major commercial success it sent a shockwave through the rock and roll world. The album’s laid back country sound with lyrics about rural living was the exact opposite of psychedelic blues rock.

When Eric Clapton heard Music from Big Pink for the first time, he felt it was what rock music was supposed to sound like. Clapton was so moved by the album, he left Cream, a psychedelic blues band who were at the peak of their popularity to go solo. Roger Waters of Pink Floyd called it the second greatest album of all time after Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967). Music from Big Pink even reached the highest echelons of popular music. George Harrison was greatly influenced by the album and his contributions to Abbey Road (1969) like “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun” and his first solo album All Things Must Pass (1970) reflect The Band’s back to basics approach to rock and roll. It wasn’t just the eschewing of psychedelia that influenced other artists, Music from Big Pink at its core features musicians who are not only at the top of their game, but who are working in total harmony with each other to create something that was bigger than their individual contribution.

Garth Hudson’s hoedown, classical, jazz, and country influences gave The Band a sound that was both timeless and old timey. The Band’s music made people nostalgic for an era that never existed. If rock and roll were around during the Civil War or Old West, it would sound like The Band. The group leaned into this rustic aesthetic with their beards and dressing in clothing reminiscent of the Old West making them stand out from their colorful psychedelic peers.

Garth Hudson’s musicianship was pivotal in making “Chest Fever” and “Up on Cripple Creek”. Hudson’s Anglican church and classical experiences are on full display on “Chest Fever”, which begins with an organ piece inspired by Johann Sebastian Bach’s composition “Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565”. Unlike other rock and R&B organists who preferred to use a Hammond B-3 organ, Garth Hudson played a Lowrey organ, the first full sized electronic organ to be manufactured because he believed the Hammond sounded too generic. The Lowrey organ is capable of bending pitches, a feature Hudson was fond of. Lowrey organs were initially developed to replace the pump organs played in theaters and churches. Garth Hudson, behind a Lowrey, brought the Anglican church to rock and roll. “Up on Cripple Creek” features another Garth Hudson innovation, but this particular innovation had ramifications beyond rock and roll. The distinctive quacking sound heard on the song is Hudson playing a keyboard instrument called clavinet through a wah-wah pedal, a device which is usually hooked up to an electric guitar which produces the distinctive wah-wah sound. Led Zeppelin’s “Dazed and Confused” and Cream’s “White Room” are classic examples of the wah-wah effect. Garth Hudson’s combination of the clavinet and the wah-wah pedal had a massive influence over the funk genre during the 1970s with artists like Stevie Wonder using the clavinet and wah-wah pedal to great effect on songs like “Superstition” and “Higher Ground”. However, in an interview decades later about the making of “Up on Cripple Creek”, Hudson was nonchalant about his influential innovation. He said the clavinet and wah-wah pedal combination was easy to do and that the sound reminded him of an old harp.

Like many geniuses, Garth Hudson had his share of quirks. He had narcolepsy, would buy orange juice but wouldn’t drink it until the pulp had settled at the bottom of the carton, and when eating a tomato would avoid eating the seeds. In the few recorded interviews Hudson gave he appears to struggle to make eye contact with the camera or with the person interviewing him. He rarely spoke and when he did it was in a mumbling monotone with a lisp and Hudson had a tendency to ramble when he did speak. Buddy Blue, a journalist for The San Diego Union Tribune compared Hudson’s manner of speech to the “oddly measured, august cadence of a 19th-century scholar”. Yet when Garth Hudson touched the keys of a piano or organ or picked up a saxophone or accordion, everyone understood and respected what he was about. Levon Helm wrote in his memoir This Wheel's On Fire (1993) that Garth Hudson turned The Band into a rock and roll orchestra. "He could've been playing with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra or Miles Davis, but he was with us, and we were lucky to have him," Robbie Roberston wrote in his autobiography Testimony (2016).

What was the key to Garth Hudson’s genius? His parents’ influence, his time playing Anglican hymns, and his classical background were undoubtedly pivotal. However, the secret to Garth Hudson’s genius is that he understood music in a way few people ever will. In a 2002 interview Hudson gave the world a rare glimpse of what was going on his head, “Different musical styles are just like different languages. I'm able to play a lot of instruments so I can learn the languages. It's all country music; it just depends on what country we're talking about.”