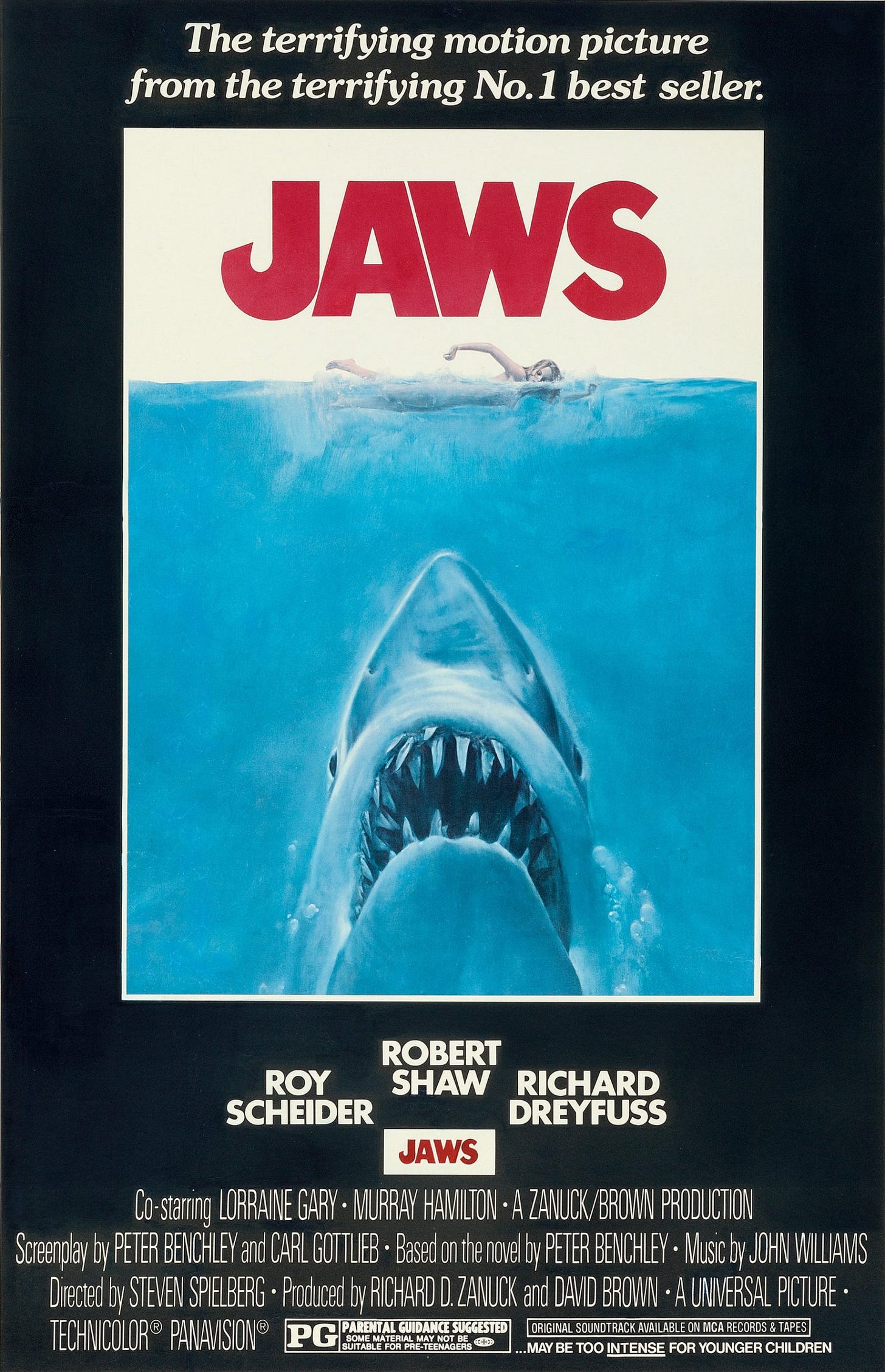

50 Years of Jaws

Jaws nearly destroyed Steven Spielberg's career before it began. 50 years and a dozen classics later, it still just might be his finest film.

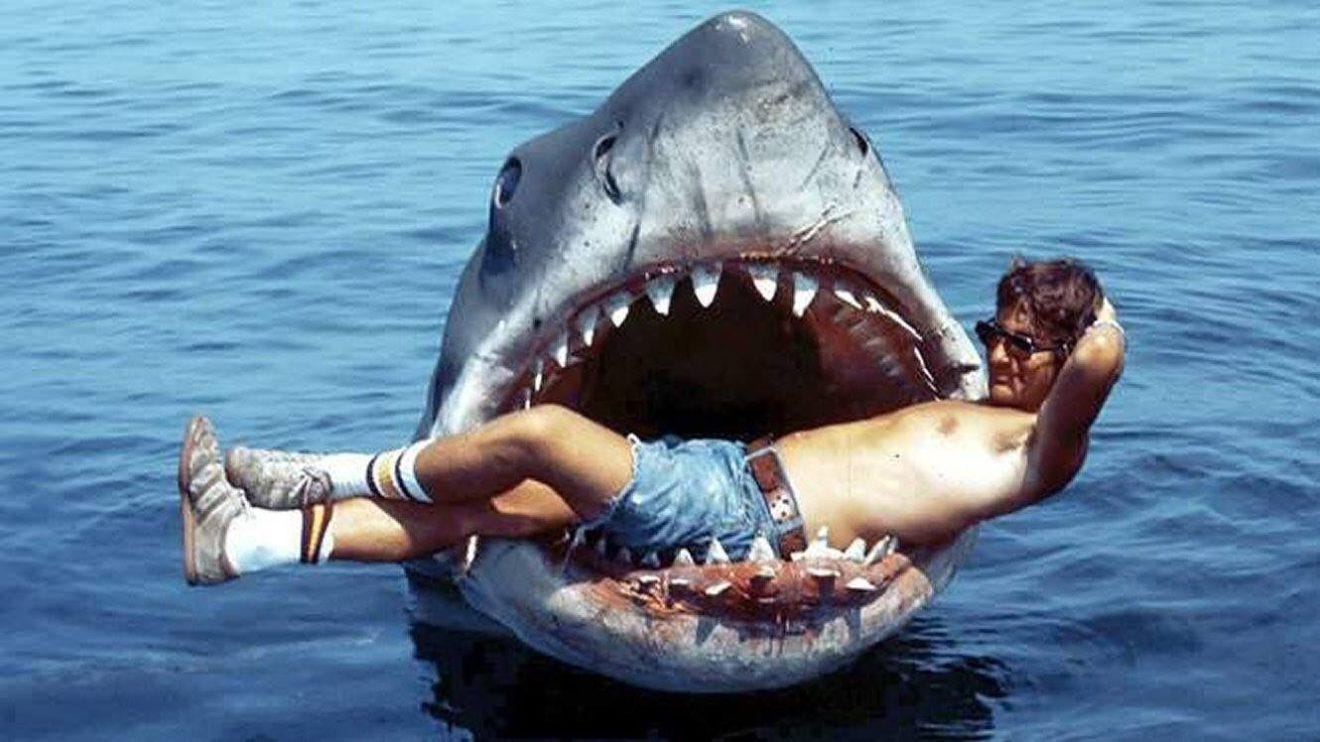

What would Alfred Hitchcock do? That’s what Steven Spielberg thought to himself as he tried to solve a dilemma on the set of Jaws (1975). Solving or not solving this dilemma would make or break his career. None of the three twenty-five-foot animatronic sharks worked. The sharks worked fine when they were tested in freshwater tanks, yet nobody considered salt water would cause the gears and circuits to malfunction. Steven Spielberg, being young and brash, insisted on filming Jaws in the Atlantic Ocean and not in a large tank in a Hollywood studio lot to ensure the film was realistic. No Hollywood film had ever been filmed on the ocean before. Spielberg thought he could control Mother Nature, and Mother Nature responded by teaching him why no one dared make a movie in the ocean. How was Spielberg going to make a movie about a killer shark with no killer shark? Days went by as the crew tried and failed to make the sharks work. Spielberg was running behind schedule and the budget was skyrocketing. When thinking about what his hero Alfred Hitchcock would have done in the same situation, Spielberg realized what his answer was. He wouldn’t show the shark at all. This one decision made Jaws one of the greatest movies of all time and it is why we’re afraid to go in the water 50 years later.

The story, the characters, the musical score, the thrills are the reason why audiences are still drawn to Jaws a half century after its release. Jaws speaks to the audience’s sense of wonder and their fears. No matter how much the world changes, people will always be captivated by the ocean’s beauty and terrified by why what lurks beneath the surface.

When casting began for Jaws, Steven Spielberg was adamant in having no major stars. He wanted the shark to be the star of the film, and the presence of major stars would hurt the sense of realism he was aiming for. However, Universal Pictures insisted that the leading actors in the film be at least well known, which Spielberg acquiesced to. Spielberg had a difficult time finding the right actor to play Chief Martin Brody and passed on dozens of actors during the screen-testing process. While at a party, Spielberg was talking with a screenwriter about the climactic scene of the film where the shark jumps onto the boat. Roy Scheider overheard the conversation and thought to himself “these guys are crazy” and knew he had to be in the movie. Spielberg, who greatly admired Schieder’s Oscar nominated performance in The French Connection (1971), recalled in an interview “Scheider…came and sat down next to me and said, ‘You look awfully depressed.’ I told him, ‘Oh no, I’m not depressed. I’m just having trouble casting my movie.’ He asked what the film was—I explained it was based on a novel called Jaws and told him the entire plot. At the end of it, Roy said, ‘Wow, that’s a great story! What about me?’ I looked at him and said, ‘Yeah, what about you? You’d make a great Chief Brody!’”

Casting Roy Scheider as Chief Brody was a stroke of genius. Scheider had an everyman appeal, which audiences related to. Scheider’s ordinariness was his greatest strength. He could be one’s neighbor, uncle, father, or coworker. In 1974, Scheider was known for only playing tough guys, but portraying Chief Brody showed audiences his comedic and sensitive side. The narrative weight of Jaws rests squarely on Scheider’s shoulders as he is in all but two scenes and his reactions to the chaos around him, his frustrations, and his triumphs make Chief Brody one of cinema’s most compelling heroes.

Although Steven Spielberg was able to find his lead actor, Jaws was rushed into production so it could be released in theaters by the summer of 1975 while the novel was still on the charts. The book was released in February 1974 and filming was due to begin in May. A production the size of Jaws needs at least eighteen months of preproduction before filming begins. Spielberg and his crew only had a few months. Nothing ended up getting completed on time including the script and casting the actors. The only actors who were on board nine days before filming began were Roy Scheider, Lorraine Gary as Ellen Brody, Murray Hamilton as Larry Vaughn, Amity’s crooked Mayor, and Susan Backline as Chrissie, the shark’s first victim. When the cameras rolled to shoot the first scene of Jaws on May 2, 1974, in Martha’s Vineyard, there was no script, the shark didn’t work, and Steven Spielberg had only fifty-five days to complete the film. “They started the shoot without a cast, without a script, and without a shark.” Richard Dreyfuss famously said.

Richard Dreyfuss was cast as Matt Hooper at the suggestion of Steven Spielberg’s friend George Lucas, who directed Dreyfuss in American Graffiti (1973). Anticipating a difficult shoot, Dreyfuss turned the part down, but changed his mind after seeing his performance in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974) which convinced him he would never be hired again upon its release. Spielberg told Dreyfuss not to read the book as the script he was rewriting with Carl Gotlieb was shaping up to be much different. Hooper in the novel couldn’t be any more different than the Hooper in the movie. In the book, Hooper is described as looking like your stereotypical handsome blonde surfer, something Dreyfuss is the exact opposite of, which is why Jan-Michael Vincent and Jeff Bridges were initially considered. When Dreyfuss was cast, Hooper was rewritten to resemble Steven Spielberg’s personality.

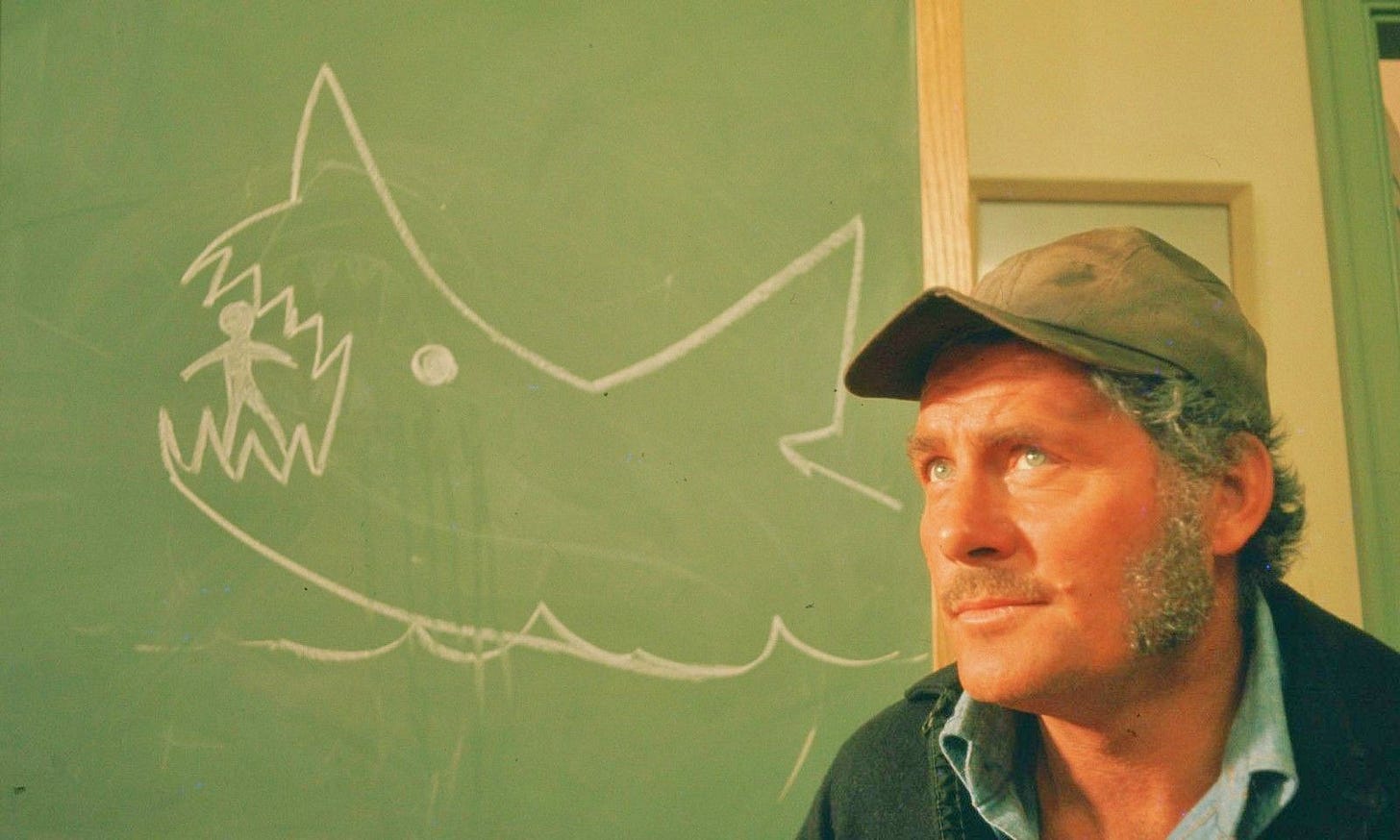

Robert Shaw was not the first actor to be considered for Quint, and he wasn’t the second or third option either. Lee Marvin was offered the part but turned it down because he wanted to do some real fishing that summer and Robert Duvall lobbied unsuccessfully for the role after turning down the role of Chief Brody. Jaws producers David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck suggested Shaw as they had just worked with him on The Sting (1973), which earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Shaw had read the book and thought it was “a piece of shit” and was going to turn down the role. However, his wife, actress Mary Ure, and his secretary urged him to reconsider. “The last time they were that enthusiastic was From Russia with Love and they were right. So, I took the part.” Shaw recalled in a Time magazine article about Jaws’ troubled production. Unfortunately, Mary Ure would not live to see her husband’s most infamous screen performance. She died at the age of 42 of an accidental overdose of barbiturates and alcohol on April 2, 1975. It was Robert Shaw who discovered her body in their London apartment.

Robert Shaw was from a generation of English theater actors who would go to the pub after every performance, drink all night, and do it all over again the next day. Shaw was about to turn 47 years old, but he looked like he was in his mid-sixties. His worn-out appearance was perfect for Quint, but Shaw’s alcoholism made managing him on set a difficult task. According to Spielberg, one of the first things Shaw said to him was “I haven’t had a drink in two months!” On their first night in Martha’s Vineyard, Shaw, Mary Ure, and their butler Eric Harrison were shot at while sleeping in their rental home. A bored local, believing the home was empty, decided to shoot the place up with his rifle. The Shaws and Harrison were unharmed, and the man was fined, but not arrested. During his time in Martha’s Vineyard, Shaw befriended local fisherman Craig Kingsbury who played fisherman Ben Gardner in the film and based his performance on him. Carl Gotlieb also used some of Kingsbury’s unique sayings for Quint’s dialogue like “It looks like a kiddy’s scissor class has cut it up for a paper doll.” When he wasn’t filming, Shaw would leave Martha’s Vineyard for Canada to escape tax evasion charges. Shaw ultimately did not make any money for his most famous performance because the IRS garnished his wages.

As filming dragged on, Richard Zanuck suspected Robert Shaw was lying about his drinking and told Spielberg as much. Zanuck and Shaw would play ping pong in-between takes and when Zanuck beat Shaw, the two men had to be separated after Shaw challenged him to a fight. Roy Scheider said Shaw was “a perfect gentleman whenever he was sober. All he needed was one drink and then he turned into a competitive son-of-a-bitch.”

Rewriting the script was a collaboration between Steven Spielberg, Carl Gotlieb, David Brown, Richard Zanuck, editor Verna Fields, her son Rick, and the actors who met in Spielberg’s rented house. Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss were almost always present during these sessions as the two were in nearly every scene of the film. Spielberg and Gotlieb completely changed the script as the former believed the characters in the novel were too unsympathetic to moviegoers. As cultural critic Kevin Mims wrote in his article for 50th anniversary of the novel, the characters Peter Benchley created were products of the bitterness and cynicism of America’s economic decline in the early 1970s. Hooper’s affair with Ellen Brody was among the subplots cut from the screen adaptation. The newly rewritten characters took on a timeless quality after the numerous rewrites.

A scene was typically written the day before it was shot, and Spielberg allowed the actors to come up with their own dialogue. It was Roy Scheider who ad-libbed the famous line “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.” According to Lorraine Gray, she came up with the line “Do you want to get drunk and fool around?” Sometimes during filming something would happen spontaneously, and Spielberg would incorporate it into the film. While setting up the dinner scene between Martin and Ellen Brody and Hooper, Roy Scheider noticed Jay Bellow, the actor portraying his son, mimicking his hand and facial movements. Scheider grabbed Spielberg, who was in the kitchen, and told him he had to get their interaction on film. Spielberg grabbed a camera and quickly shot the scene, which in just ninety seconds and without a word of dialogue, demonstrates what a loving family the Brodys are. Another memorable line, which was improvised, came from Robert Shaw. Before shooting the scene where Brody, Hooper, and Quint disembark to kill the shark, Spielberg told Shaw to come up with a way to antagonize Ellen Brody. When the camera rolled Shaw recited a limerick:

Here lies the body of Mary Lee, died at the age of a hundred and three. For fifteen years she kept her virginity; not a bad record for this vicinity.

When asked for the source of the limerick so the production could secure the rights for it, Shaw replied it wouldn’t be necessary because the limerick came from an old gravestone in Ireland.

Beginning a film without a finished script should have resulted in a disaster no matter how talented the cast and crew are. Yet, the cast and crew of Jaws were uniquely talented, and they were in the right place and right time to capture lightning in a bottle.

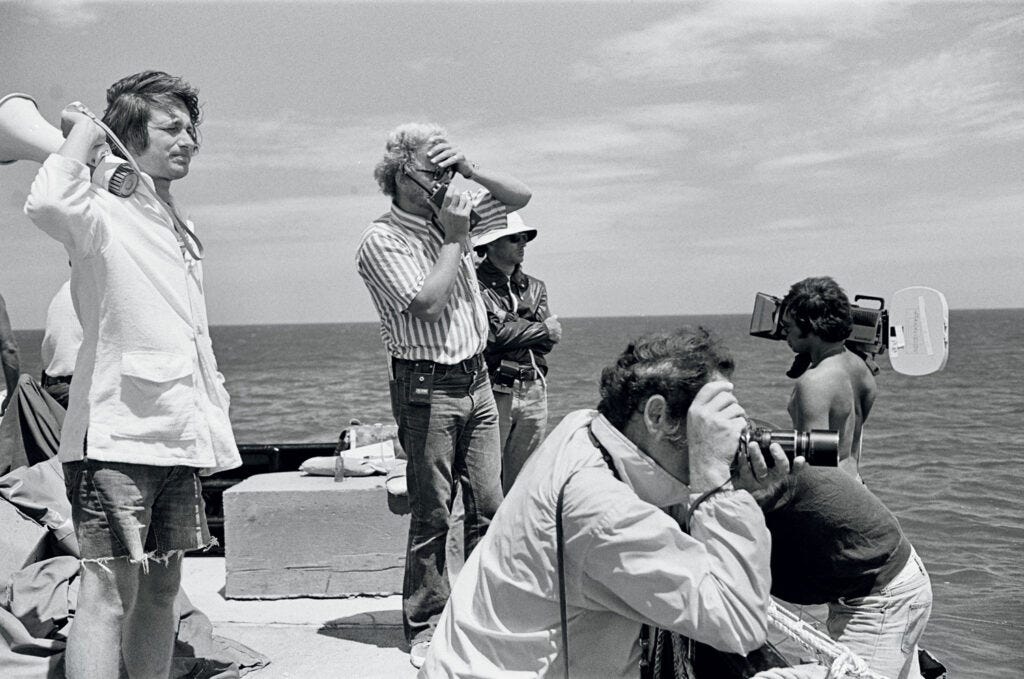

Filming went smoothly while production was on land, but filming in the ocean caused a litany of unforeseen problems to arise. While Spielberg was able to remedy the problem of the malfunctioning shark by not showing it at all, many weeks went by before he came to this conclusion and more time was needed for him to plan the new shark attack scenes. Filming the second half of Jaws when Chief Brody, Hooper, and Quint are hunting the shark at sea halted production to a snail’s pace. Cameras mounted on a tripod could not hold steady when the waves rocked Quint’s boat, the Orca, back and forth, so the decision was made to shoot everything with handheld cameras. Transporting equipment to and from the ocean was a logistical nightmare and if the crew needed any equipment at the last minute, they had to go back to the mainland to retrieve it, which ate up precious time. A small filmmaking navy was assembled on the fly to facilitate production. Anchors were attached to the Orca and the boats the camera crew were on to prevent them from drifting in the water, but a strong current would drag the anchors across the bottom of the ocean and still knock the boats out of place. By the time the boats were put back into their proper place, the sun had changed position, and the day would be lost.

At this point in the film, the Orca is the only vessel at sea and the audience needed to feel the three protagonists’ isolation. However, there were other boaters on the horizon during filming and shooting would have to be halted whenever they appeared in the frame. Today, those boats could easily be erased with digital effects. That wasn’t the case in 1975. The cast and crew had to wait…and wait. Oftentimes, as soon as a boat left the frame, another one would be about to enter leaving Spielberg to make the decision to cancel the shoot or try and hurry to complete the shot. Days went by where nothing was filmed. “We all gained a tremendous respect for the sea, for nature, for currents and tides, for waves, for rain and sun and overexposure to both.” Steven Spielberg said in the retrospective documentary The Shark is Still Working (2007). In the same documentary Roy Scheider said, “We thought we were going to be there for the rest of our lives.”

During a 1974 onset interview, Spielberg did not sugarcoat the difficulties of shooting on the ocean “The sea conditions have been so impossible that it’s really hurt our schedule and put a general somber note behind the scenes on the production because we’ve been here a hundred and five shooting days and we were only scheduled for something like sixty-five or seventy.” The crew was eventually able to get the sharks to work during this point in production, but only for brief intervals. According to Richard Zanuck “What you see in the finished picture is practically every frame of usable footage of the shark.”

The lengthy shooting delays only exacerbated Robert Shaw’s drinking. When asked what he and the rest of the cast did during the downtime in an onset interview, Shaw answered “Well scotch, vodka, gin, whatever we all have different methods. I do tend to drink…Roy does exercises and sunbathes and Dreyfuss talks. Dreyfuss just talks.”

Robert Shaw loved to get under people’s skin, and he found a perfect target for his shenanigans in Richard Dreyfuss. Roy Schieder believed Shaw disliked Dreyfuss because he was a “young punk” who, unlike him, had no theater experience and therefore wasn’t a serious actor. Dreyfuss’ bragging about the rave reviews he was receiving for The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz also irked the highly competitive Shaw. Dreyfuss couldn’t make sense of Shaw’s behavior. Off the set, Dreyfuss thought he was the nicest man in the world, but when they arrived on the Orca, Shaw would become a totally different person. According to Roy Scheider, Shaw insulted Dreyfuss, saying “You eat, you drink, you’re fat, and you’re sloppy. At your age it’s criminal. Why you couldn’t even do ten good pushups.” When Dreyfuss responded he could do twenty pushups, Shaw responded, “You can do twenty good pushups?” and turned to Scheider and said “Okay Roy, you’re the referee. Tomorrow morning we’re gonna see if Dreyfuss can do twenty good pushups.” When Shaw walked away, Scheider told Dreyfuss “You know how many people can do twenty good pushups? You are not one of them.”

Robert Shaw also played mind games. Right before filming a scene, Shaw would whisper “mind your mannerisms” to Dreyfuss causing him to be conscious of his body language while he simultaneously tried to remember what he was supposed to be doing. Shaw also dared Dreyfuss to jump off the mast of the Orca for a hundred dollars and upped the amount each time he was refused. When Dreyfuss finally gave into Shaw’s badgering, Steven Spielberg stepped and told him was not going to jump off the mast under any circumstances. One day as Shaw, with a glass bourbon in his hand, was walking on a plank to board the Orca, asked Dreyfuss for help getting on the boat. Dreyfuss said “You want me to help you out” and snatched the glass from Shaw’s hand and threw it in the water. Shaw responded later that day by spraying Dreyfuss in the face with a firehose. Yet, despite all the hazing, Dreyfuss could not help but admire Shaw and in every interview where he discusses their turbulent relationship, there’s a gleam in his eye and a little smile on his face.

The tensions between Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw mirrored Hooper and Quint’s mutual contempt for one another. Just like how Shaw didn’t see Dreyfuss as a real actor, Quint doesn’t see Hooper as a real fisherman because of his college degree and reliance on technology. Hooper, much like Dreyfuss, senses that Quint is overcompensating for his insecurity. Whether Shaw antagonized Dreyfuss on purpose to make their onscreen chemistry better or because he genuinely disliked him is unknown, but the tension undoubtedly improved both men’s performances as they didn’t have to act when they insulted each other.

Chief Brody, Hooper, and Quint’s strengths and weaknesses are on full display as they try to kill the seemingly invulnerable shark. Fifty years later audiences find these qualities so relatable. Brody must overcome his fear of the water and is a totally inept seamen, just like most of the audience. Hooper is too smart for his own good, but the light he attaches to the barrels which brings the shark to the surface gives him and his two shipmates a temporary leg up on the shark. Quint and his experience briefly challenge the shark, but his stubbornness and his insistence on going it alone proves to be his undoing.

As the shooting dragged on and the budget ballooned, a demoralized and depressed Steven Spielberg began hearing rumors from Hollywood that his career was over. Producers David Brown and Richard Zanuck had placed their faith in him, and he was blowing it. Zanuck in particular believed the young director had great potential and would put a new spin on the adventure film genre. He lobbied Universal executives, who were reticent about hiring an inexperienced director, to helm the adaptation of a bestselling novel to take a chance on Spielberg. As Robert Shaw and Richard Dreyfuss bickered and Spielberg feared he would be fired every day he arrived on set, Roy Scheider’s professionalism kept the production together and Richard Zanuck kept Universal off Spielberg’s back.

Just when it looked like all hope was lost, one pivotal scene brought the production together. The idea for the Indianapolis Speech came from Howard Sackler, who was hired to rewrite Peter Benchley’s script before Carl Gotlieb took over. The writing for the monologue became a collaborative effort after Sackler’s departure. According to Richard Dreyfuss, Steven Spielberg enlisted his friends Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and Brian DePalma to help with the speech. Roy Schieder claimed he contributed the “like a doll’s eyes” line. Spielberg didn’t get a breakthrough until he sent the script to his friend, screenwriter John Milius, who wrote Jeremiah Johnson (1972), Apocalypse Now (1979), and wrote and directed Conan the Barbarian (1982). Milius, an avid reader of military history, was the perfect person for the job and he wrote the speech with little effort. However, it was eight pages long, which was too lengthy to film. Robert Shaw, who was a playwright, cut Milius’ speech down to an acceptable length.

Before the evening shoot for the monologue, Robert Shaw approached Steven Spielberg and asked him for permission to have a few drinks. Shaw said since Quint, Hooper, and Chief Brody are all drinking it would make sense for him to be a little drunk. Why Shaw felt the need to ask permission to drink is a mystery seeing as he was drunk for most of his time on set. Spielberg, being young and naive, agreed and an hour later two members of the crew carried a barely conscious Shaw onto the set as the cameras were about to roll. After a couple of takes, Spielberg realized Shaw was in no condition to perform and wrapped early. At two in the morning Shaw called Spielberg and apologized for embarrassing him and confessed he was black out drunk. He asked Spielberg to give it another shot, and the next morning Shaw showed up sober and nailed the speech in four takes. Prior to the Indianapolis Speech, Quint is a one-dimensional Captain Ahab rip off. The monologue gives the audience an unforgettable justification as to why Quint has such a seething hatred for sharks. The fact, the Indianapolis Speech did not earn Robert Shaw an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor is one of the more underrated snubs in the Academy’s history.

Fortunes turned in the production’s favor after filming the Indianapolis Speech and for the first time the cast and crew began to feel they might have something special on their hands. On October 6, 1974, filming for Jaws wrapped. The 55-day shoot ended up lasting 159 days and the $4 million budget had skyrocketed to $9 million. Steven Spielberg was not present for the final scene where the shark is blown up because he thought his crew was going to throw him in the ocean and leave him there. Letting the crew shoot the final scene has been a Spielberg tradition ever since.

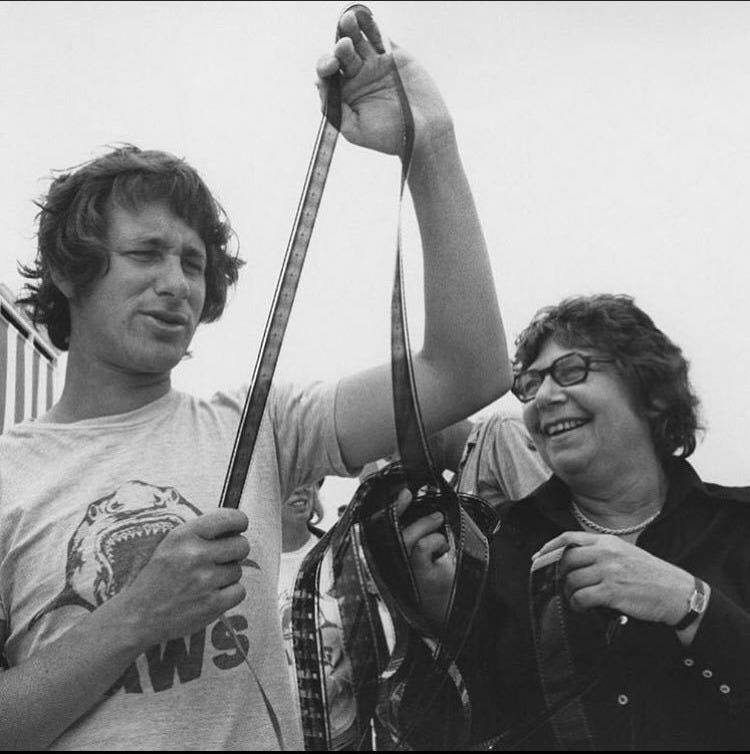

Editor Verna Fields and Steven Spielberg cut Jaws in Fields’ pool house. It was Fields’ keen eye which made the film flow in the final edit. She was able to seamlessly splice together footage to form a complete scene without the audience realizing the individual shots were filmed days and sometimes weeks apart.

Verna Fields was pivotal to how violence was portrayed onscreen in Jaws. The violence is one of the most unique aspects of Jaws because the film isn’t as bloody as people believe it is, which was a byproduct of the shark not working. There is not one drop of blood onscreen when the shark attacks the young skinny dipper in the opening scene and the shark isn’t shown onscreen. The audience sees the shark stalk the young woman from its point of view up until the point it attacks her and then Steven Spielberg leaves it up to the audience to imagine what is happening beneath the water. The young woman’s screams of terror and agony as she tries to escape from the shark tearing into her flesh are more powerful and disturbing than blood could ever be. When Spielberg does show blood, it is only for a brief moment and just enough to shock the audience. Then Verna Fields cuts away before the audience can focus on it. The prime example of this is when the shark claims its next victim, Alex Kitner. Once again Spielberg shows the shark hunting for its prey amongst a litany of swimmers right up until the point it attacks the young boy. Blood spewing from the water as the boy is dragged into the depths of the ocean is shown briefly and then the scene cuts to the horrified reaction of the beach goers who desperately swim to safety. The horror does not come from the violence; it comes from the audience’s anticipation and the other characters’ reaction to it. The restraint Spielberg shows in presenting blood onscreen pays off during Quint’s death scene, which lasts ten seconds longer than it probably should. There is no music, just the sound of Quint’s screams as the shark devours him, screams which are all the more shocking as they shouldn’t be coming from such a tough and fearless character. Then there’s the sound of the sickening crunch when the shark bites him in half.

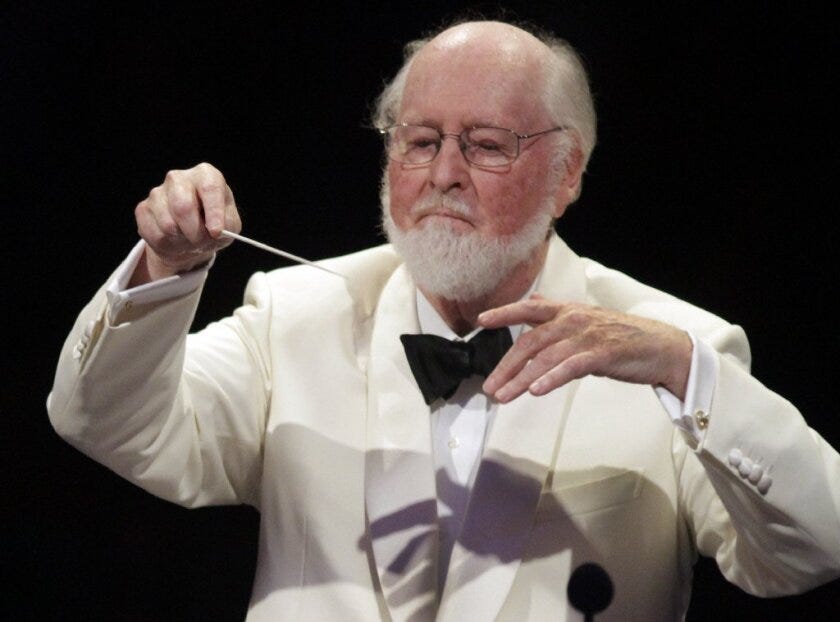

John Williams’ score is Jaws’ defining component. The iconic main theme has only two notes, but that’s all Williams needed to scare generations of moviegoers. Steve Spielberg, who had worked with Williams on his first feature film The Sugarland Express (1974), laughed when he heard Williams play the main theme on the piano and thought it was a joke. After hearing Williams play the theme again, Spielberg realized it was perfect. Williams composed the theme with the idea that the tempo could be altered to suit a specific scene. The theme could be played slower to build anticipation or faster to signal the shark was an immediate danger. The theme was also a godsend for Spielberg when he decided to limit the use of the shark onscreen. All he had to do was put the camera in the water, play Williams’ theme, and the audience’s hearts would start racing.

However, it’s not just the main theme which makes Jaws’ score one of best in film history. Williams did not view Jaws as a horror or thriller film. He believed it was an adventure film at its very core. When Chief Brody, Hooper, and Quint begin their hunt for the shark, Williams’ score doesn’t scare the audience, it exhilarates them as he brings them on the same thrilling journey the protagonists are on. Nothing demonstrates John Williams’ impact on Jaws more than watching the previously mentioned scene without music. The scene comes across like a quasi-documentary in its absence, but Willams’ score brings the movie alive. Steven Spielberg himself later said John Williams was responsible for fifty percent of Jaws’ success.

Universal Pictures knew they had a hit on their hands before Jaws was even released. “I want this picture running all summer long.” Universal Chairman Les Wasserman was quoted as saying after attending a preview screening. Universal Pictures promoted the film with an unprecedented advertising campaign spending $1.8 million to market it. $700,000 alone was spent on television advertisements during prime time hours from June 18-20th, which was an unheard-of amount of money for a television marketing campaign at that time. There were also only three channels during this time so everyone who was watching television saw the trailer for Jaws. Merchandise like t-shirts, a soundtrack album, beach towels, and posters were released to ensure the film would always be on the audience’s mind even after they exited the theater or if they hadn’t seen the film at all. Before Jaws, merchandise was an afterthought for film studios, but after the film’s success, merchandise became one of the pillars of every big budget film’s advertising campaigns.

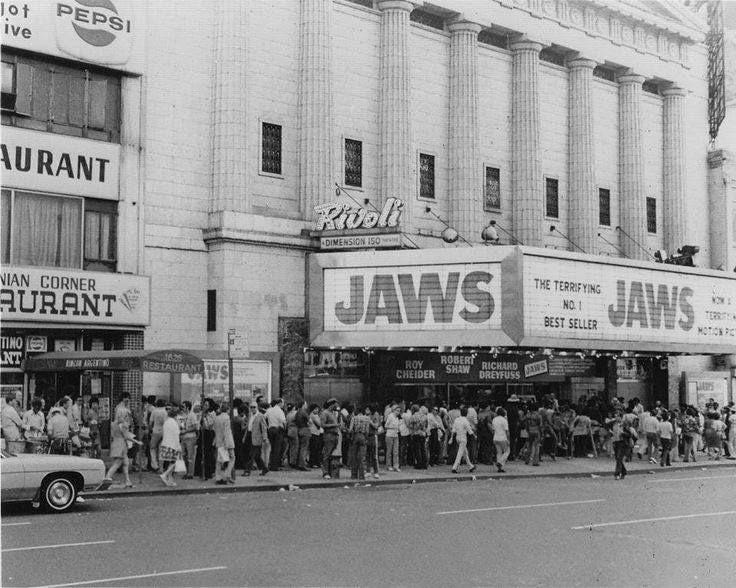

Universal also made another of many unprecedented decisions when they released Jaws on 409 screens across the United States on June 20, 1975. Prior to Jaws, films were released in a select few markets first before gradually expanding across the country over a period of multiple weeks. The film was initially going to be released in 1,000 theaters, but Universal cut the number in half. “I don’t want people in Palm Springs to see the picture in Palm Springs. I want them to get in their cars and drive to see it in Hollywood.” Les Wasserman said of the movie’s release strategy. Jaws was also released in the summer, which was a downtime of year for the film industry because it’s when people are outside and travelling.

The hype prior to and during Jaws’ theatrical run paid off. It grossed $7.8 million on its opening weekend, a record at that time. The film cost $9 million to make. It grossed $21,116,354 in its first ten days. Another record for that time. In just 78 days, Jaws surpassed The Godfather as the highest grossing film ever at the North American box office. The Godfather (1972) earned $86 million over the course of its initial release. Jaws was the first film to ever gross $100 million, and it spent 14 consecutive weeks as the number one film at the United States box office. It literally owned the summer. When the summer of 1975 ended, Jaws had grossed $123.1 million domestically. Jaws’ success was so unprecedented the press had to come up with a term to describe it. They settled on the term blockbuster because of the long lines which stretched for blocks around movie theaters across the world.

In December 1975, Jaws was released internationally, and its success overseas was identical to its success in the United States. The film broke box office records in Singapore, New Zealand, Japan, Spain, and Mexico. By January 11, 1976, Jaws surpassed The Godfather as the highest grossing film made worldwide. The records wouldn’t last long. Star Wars (1977) broke them all when it was released. More higher grossing films have been released since, but Jaws is still the blueprint for how major films are marketed. Jaws created the concept of the summer blockbuster film, and for better or worse, the film industry changed its entire business model in an attempt to replicate its success.

Across all of Jaws’ theatrical releases, it has grossed $484 million. This does not count the amount of money it has grossed through VHS, DVD, Blu-Ray, video on demand sales, and the sale of television and streaming rights. On September 3, 2022, Jaws was re-released in select theaters for the weekend for National Theater Day, a day where tickets sold at all movie theaters cost $3. It grossed $2.6 million over three days and finished as the tenth highest gross film of that weekend. Even nearly a half century after its release Jaws proves to be irresistible to film goers. Jaws will be rereleased for the week of August 29th-September 4th, 2025, where it will undoubtedly be one of the week’s highest grossing films.

It is easy to see Jaws’ box office numbers and be floored by the amount of money it made for its time, but what are the numbers behind those numbers? To give an idea of how many people saw Jaws in North America during the summer of 1975, it is estimated that 25 million tickets were sold in its first 38 days of release. 67 million tickets overall were sold during its initial run in the summer of 1975. The estimated population of the United States in 1975, was 219 million, meaning 31% of Americans saw Jaws. Many of these tickets sold were also purchased by people who watched the film multiple times, but there is no accounting for the percentage of Americans who saw Jaws more than once in 1975.

When Jaws appeared on television for the first time on ABC on November 4, 1979, an estimated 29.7 million viewers tuned in. According to the New York Times, Jaws garnered more viewers than that year’s final game of the World Series between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Baltimore Orioles and 57% of all television viewers tuned into ABC to watch the film. Even more people have seen Jaws on television as it has become a regular staple of summer programming. Millions more have watched it on home video or on a streaming platform. There’s a legitimate case to be made that Jaws is the most watched movie ever made.

Ask anyone who was alive during The Summer of 1975, and they will tell you they saw Jaws at the theater. They’ll tell you who they saw it with, they’ll tell you where they sat in the theater, they’ll talk about how people in the theater reacted to the film’s most iconic moments, and they’ll talk about Jaws like it was a pivotal part of their summer. It’s a cross-generational touchstone. The Summer of 1975 was the summer of Jaws. It didn’t matter if you were young, old, black, white, man, woman, or child. You saw Jaws. It didn’t matter if you were a housewife, an elderly couple watching their grandkids on the weekend, a WASP executive for General Motors, or a black man working on the line for General Motors. It didn’t matter if you were an Italian or Puerto Rican construction worker from Brooklyn, or a cowboy from Oklahoma. You saw Jaws in the Summer of 1975, and you at least had that in common with people you otherwise couldn’t relate to. Social media and the fracturing of our culture have taken away these shared cultural experiences from us and that’s a tragedy. Sports still bring people together, but not everyone is a fan and even sports become a tired subject after a while.

In an ever increasingly isolated society, we need films like Jaws to not only talk to our friends, coworkers, and families about, but to give us a good conversation starter when we chat with strangers. Talking about our favorite characters, our favorite scenes, the soundtrack, the brilliance of Steven Spielberg’s first masterpiece gives us something pleasant to share with each other. That world’s gone now. Maybe one day humanity will realize we need these shared cultural experiences and slowly rebuild this part of our culture because without these shared experiences, the world is duller and more isolated. Anyways, I’m going to be watching Jaws tonight at 8 P.M. on NBC. I hope you will all join me.